Google 25 Principles Of Mobile App Design

Deep dive: Mobile design principles and best practices

Most mobile experiences suffer from poor UX because their creators failed to observe mobile UX design principles and best practices. These fundamental tenets of mobile usability have been developed over time through meticulous research and user testing. Applying them with rigor will enable designers to create better mobile user experiences.

![]()

With nearly 9 million apps at people's fingertips, it's tough out there for a mobile app designer. At least a thousand new apps pour into the Google Play Store and Apple's App Store each day. Yet, more than 75% of them are downloaded, opened once, and never used again. Most of this can be attributed to poor usability.

Take just one industry: eCommerce. With 3. 5 billion smartphones globally, it's losing hundreds of billions of dollars every year by not following UX design best practices. The site is either too slow, the search is broken, the UI is indecipherable, or the navigation is awful.

Things looked pretty dire for an unlucky development team when people kept leaving 1-star reviews on the app store about their expensive creation. The reviews complained that the app was "too slow." Desperately wanting to correct the situation, the team rewrote the app over several months at an eye-watering expense.

When they tested the app again, they were mortified. It turns out people meant that the navigation was awkward, using the UI was cumbersome, and finding things was "too slow." It was a UX issue, not a speed issue!

If they'd followed mobile UX design best practices, they could have produced an app with superior usability. Following "golden rules" and standards would have improved their mobile UX, and they would have received better reviews.

"Users try out a lot of apps but decide which ones they want to stop using within the first 3–7 days. For decent apps, the majority of users retained for seven days stick around much longer. The key to success is to get the users hooked during that critical early period." –Ankit Jain

People don't want to learn a new mobile interface every time they open an app. They want to be entertained or get things done. They want products that are easy and "just work."

Mobile users want instant access to everything. It's estimated that people check their phones about 80 times a day! Because they're often used for short bursts of activity, frictionless designs with great UX succeed more.

Neuroscientists say our brains are energy hogs . The brain evolved over millennia to be as efficient as possible — to save energy. People crave consistency and ease-of-use because our brains prefer the least amount of friction.

Unquestionably, everyone wants their app to succeed. But if something is unusable, it means increased friction, and people will move on. No matter how aesthetically-pleasing the visual design, how fancy a micro animation is — if the app's usability is flawed, the experience will be broken.

"Experience is critical, for it determines how fondly people remember their interactions." — Don Norman in The Design of Everyday Things

Coined by Jakob Nielsen, Jakob's Law states that "Users spend most of their time on other apps. People prefer your app to work the same way as all the other apps they already know."

The most popular and successful apps follow mobile UX design best practices because these "tried and true" standards mean that people don't have to re-learn a UI. It's not about cloning other apps. It's about not breaking expected patterns unless it provides significant value.

The Significance of Mobile Usability

Usability is a quality attribute in UX made up of many components. There are many, but let's dive into five crucial ones:

● Learnability: How easy is it for people to accomplish basic tasks the first time?

● Efficiency: How quickly can people perform tasks?

● Memorability: When people return to the design after a period of not using it, how easily can they reestablish proficiency?

● Error Recovery: How many errors do users make, how severe are they, and how easily can people recover from them?

● Satisfaction: How pleasant is it to use the design? Does it help people accomplish their tasks? Was it a satisfying interaction?

Mobile Navigation

Let's dive deeper into usability. First up, navigation. There's a saying in the UX world, "discoverability always wins." Discoverability in UX refers to a UI where every possible interaction is crystal clear to users. If people can't find something, "it doesn't exist." A hamburger menu, for example, is detrimental to usability because it's considered hidden navigation. It impairs usability because it has low discoverability and a high interaction cost.

"The interaction cost of accessing a desired piece of information is higher on mobile than on the desktop." –The Nielsen Norman Group

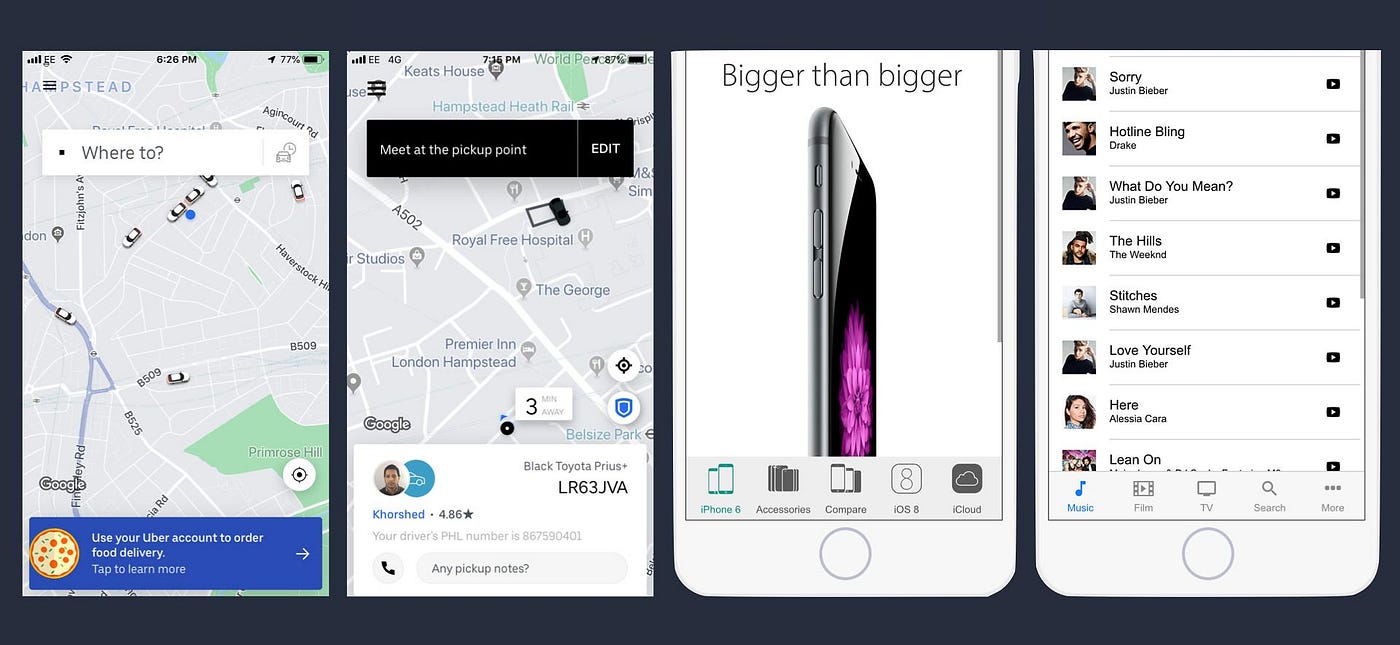

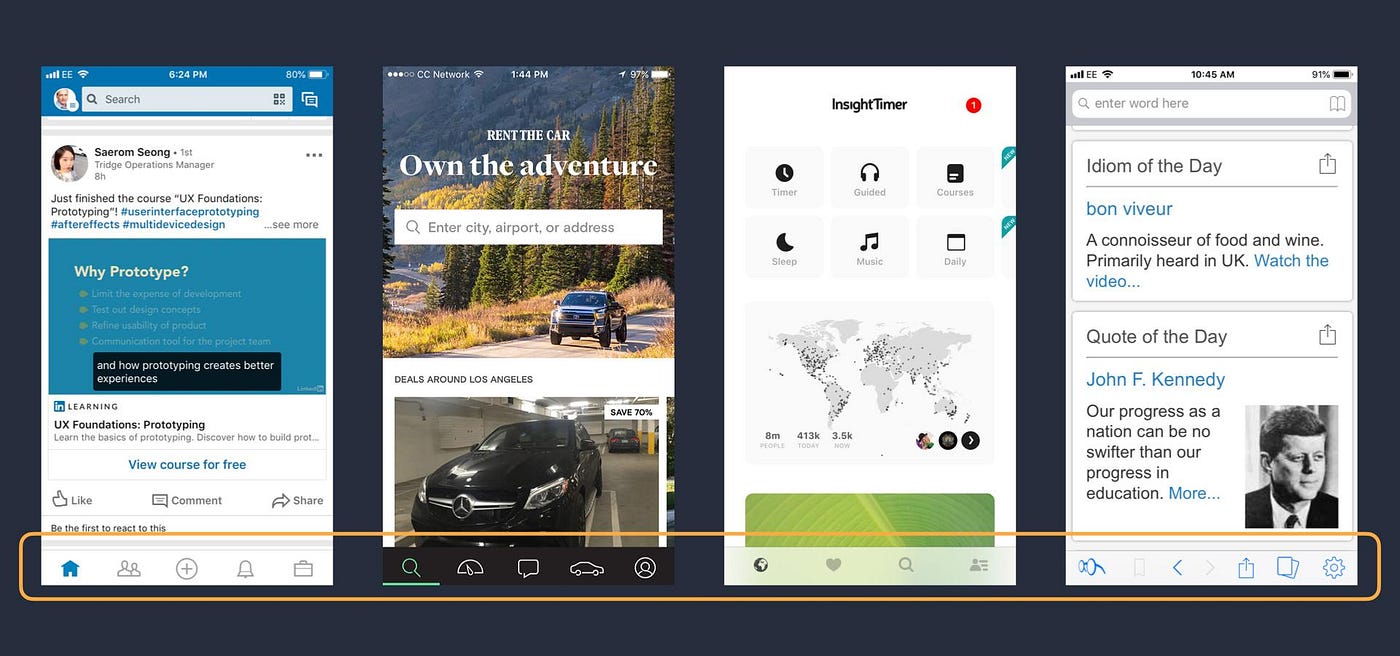

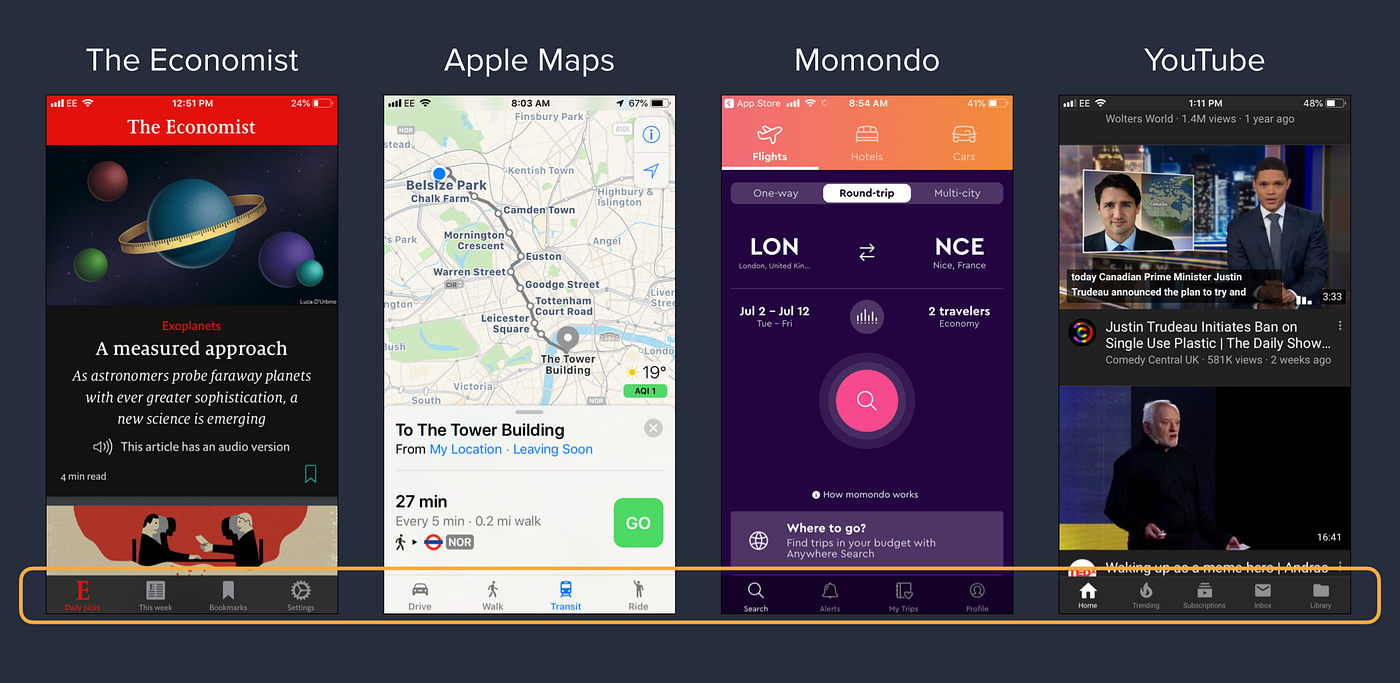

Among many mobile navigation patterns, the "tabbed view" is a popular one. Content is divided into tabs (like desktop devices), and users navigate between the tabs from a toolbar accessible on any screen.

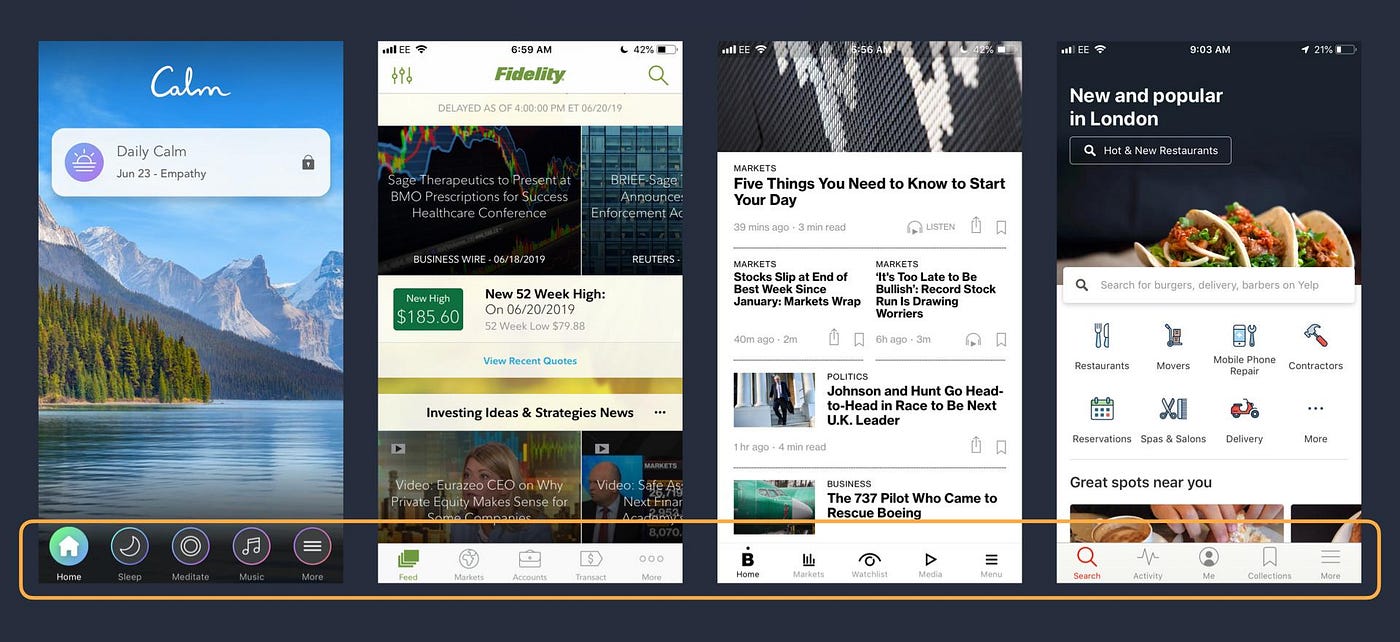

Mobile usability experts have performed countless tests between tab bars (aka the bottom navigation bar on Android) used for the "tabbed view" and the hamburger menu for mobile navigation. Which one came out on top? It was the tab bar (seen above on the right). Why? Because it exposes the primary navigation and allows movement between primary destinations in an app. If unavoidable, designers can use a hamburger menu on the tab bar for secondary, less important options.

"A tab bar is a good way to flatten your information hierarchy and provide access to several peer information categories or modes at once." — Apple Human Interface Guidelines.

A particular form of navigation may have become ubiquitous, but it doesn't mean it's the most efficient. After countless tests, Facebook and Spotify decided that a hamburger menu should not be used as an app's primary navigation. They require significant effort from the user. They have to discover it, tap it to open, read through all the available options, make a decision, and tap again to go to the option selected.

Kebab menus belong to the same group as hamburger menus. They are also seen everywhere, and people are getting used to them, but they still decrease discoverability and, therefore, negatively impact mobile UX. It's best only to use a kebab menu as a last resort. People don't see them, so may as well not have them!

When designers don't know how to properly structure mobile content (its information architecture) and design efficient navigation, they typically use hamburger menus and kebabs as a design crutch. Astonishingly, some UIs sport not one but two kebabs, as the last screen below demonstrates.

Icons in Mobile UIs

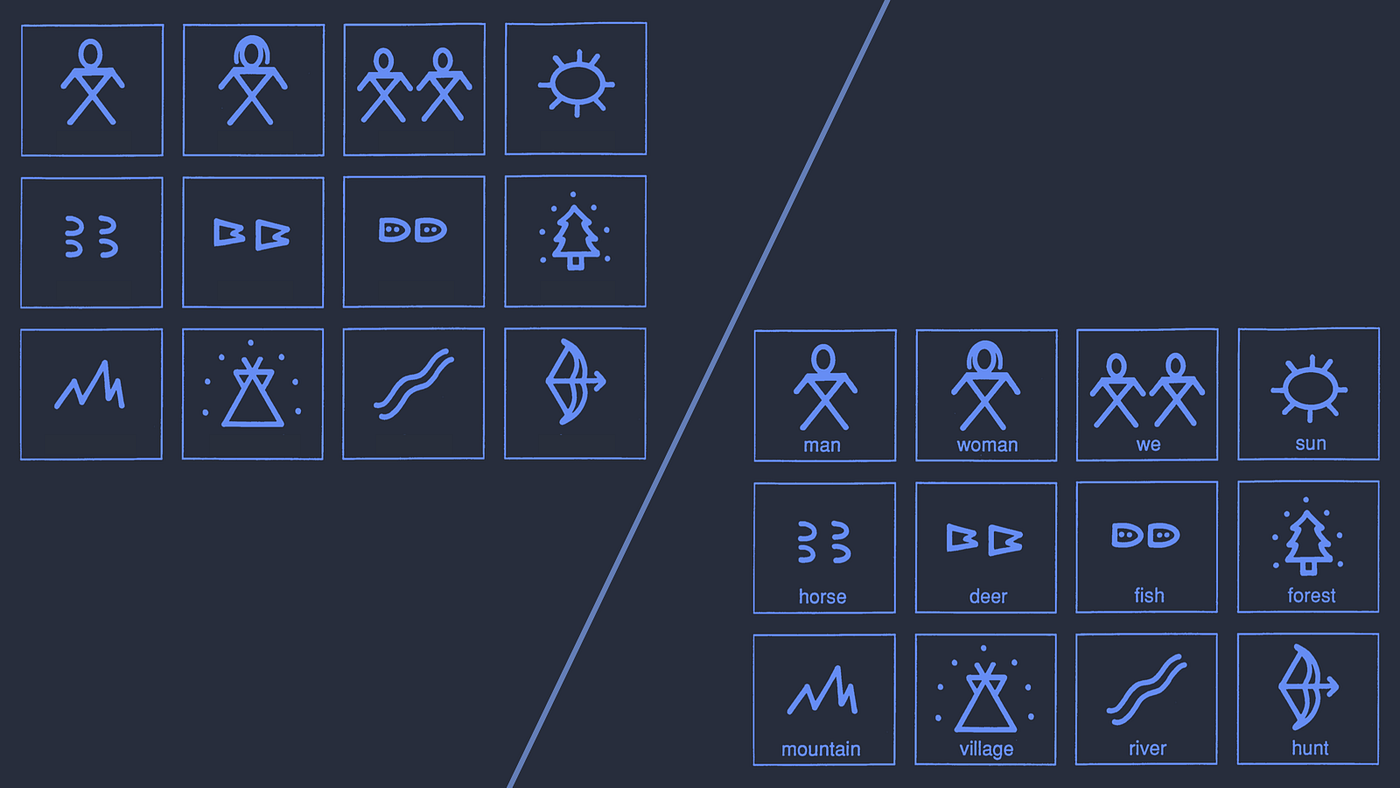

Since ancient times, people have used symbols to communicate with each other. It is a scientific fact that our brain processes (recognizes) symbols about 1000x faster than reading text. The Greeks, Egyptians, and Chinese used symbols in some of the earliest writings.

On the left side above are some symbols that Native Americans used to communicate. How many can you decipher as to their meaning? Maybe the top row — not much beyond that.

But when we see the descriptions in the lower right, they make more sense, and recognition becomes a lot faster. We'll see in a second why this is important.

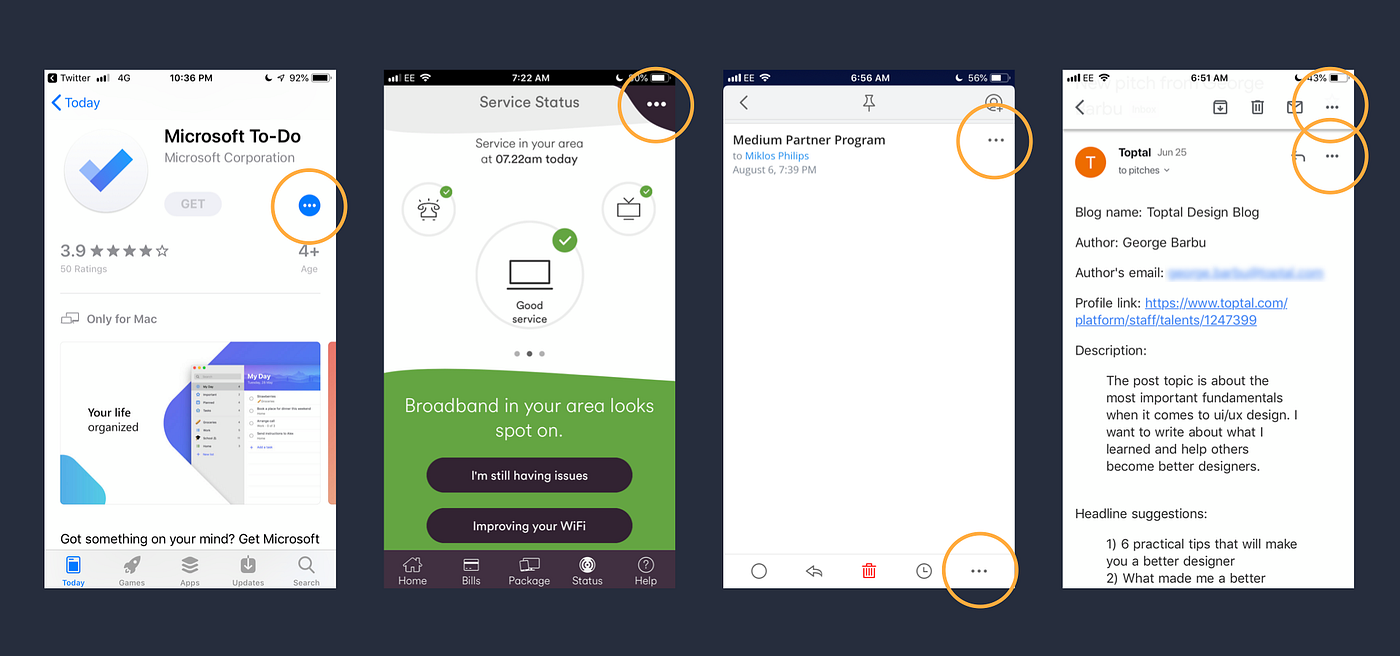

Whereas universal icons are instantly recognizable, non-universal, unlabeled icons are a guessing game. People are stopped in their tracks. Unlabeled icons in a UI are equivalent to throwing a roadblock into a user's path because they have to stop to decipher their meaning. User flow comes to a screeching halt!

The screens below from some popular apps show unlabeled icons. Try to guess what they all mean and where they would take you!

Recognition Rather Than Recall

Recognition refers to our ability to "recognize" an event or piece of information as being familiar. At the same time, recall is much more of a "cognitive burden" that involves pulling related details from memory. Showing users things they can recognize improves usability over needing to recall items from scratch.

For example, using icons in a UI is powerful because it allows for the instant recognition of a symbol. If a standard warning sign icon is shown in a dialog, it immediately makes the user pay attention because the next action may be destructive. But if an icon is designed to force users to recall and decipher meaning — a hand held up, for example, instead of the warning icon — it decreases efficiency and usability.

There's also a concept in UX called "value vs. pain" — how much investment one is willing to make to find out where an icon leads. Most people do not want to learn and memorize what an icon means in one app when using many different apps every day.

The mobile UX design best practice for icons is: always label icons with text. Labeled icons ensure that meaning is conveyed quickly and easily and that they are consistently understood. Most big-brand, popular apps do it.

Speed

On mobile, speed is king. Milliseconds earn millions. In mobile eCommerce, even a one-second delay in load time can negatively impact conversions by 20%. If a slow mobile experience drives customers away, a fast mobile experience can help attract and keep them.

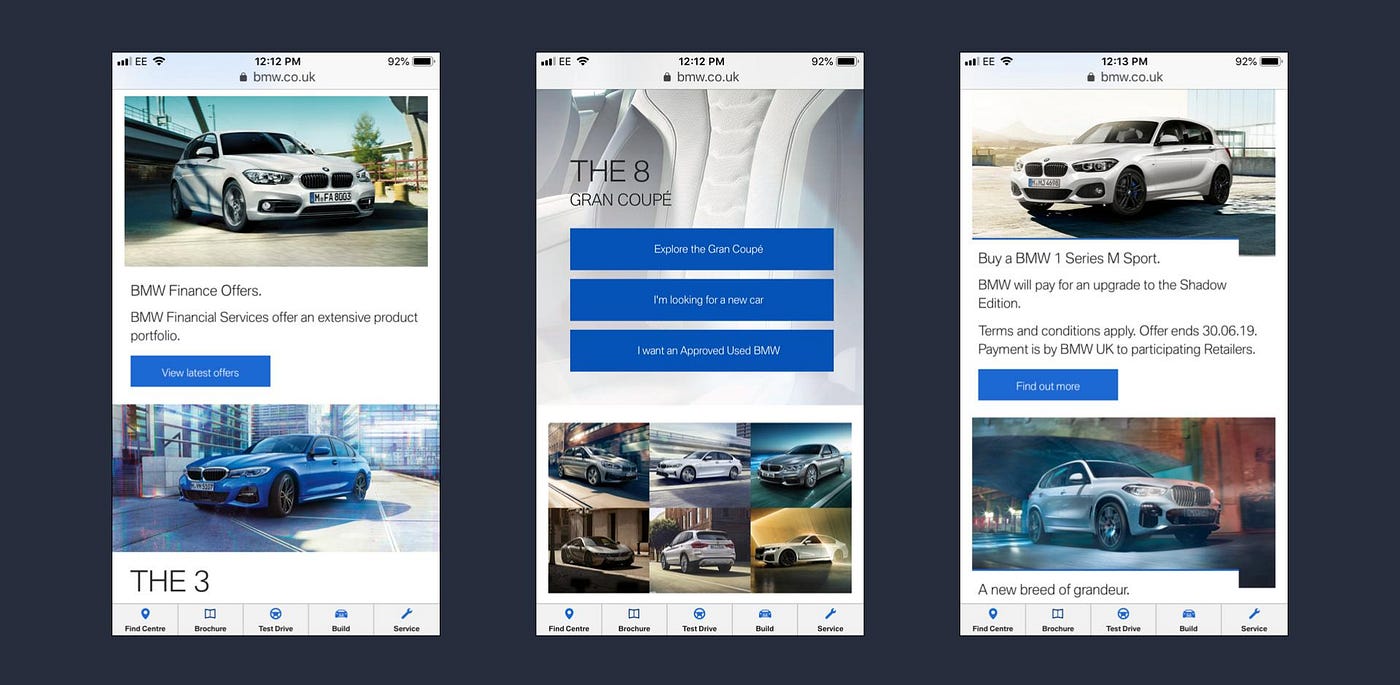

BMW listened to this recommendation and supercharged its mobile site using Accelerated Mobile Pages (AMP) and Progressive Web Apps (PWA) — two state-of-the-art technologies for speedy mobile site experiences. After they did this, the proportion of people clicking through to a BMW sales site soared from 8% to 30%, nearly 4X higher than previously.

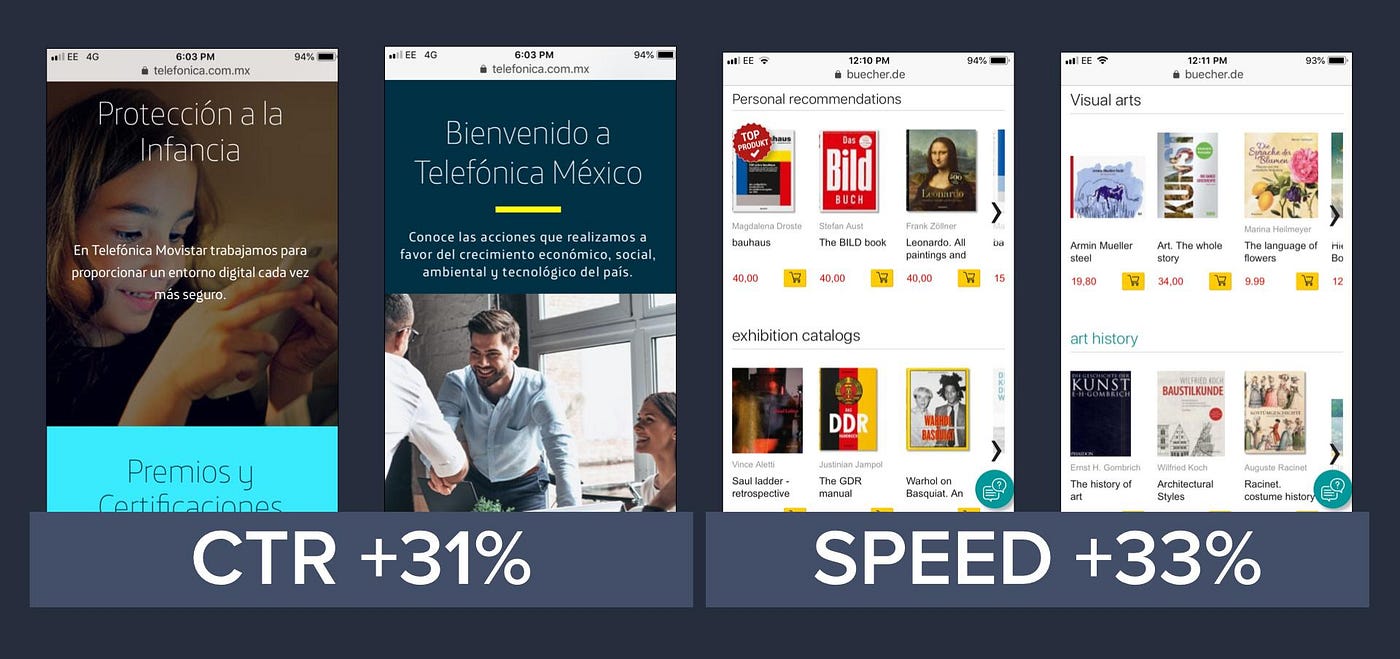

With AMP (accelerated mobile pages), Telefónica, one of the largest mobile network providers in the world, improved load times for its mobile site by 70%. This speed boost helped the company increase click-through rates by 31%!

German eCommerce site Bücher was able to speed up its site by 33% by using "lazy loading" of images, and as a result, increased their book sales. The critical takeaway for designers is to work with developers to improve the speed of mobile sites and apps because it will dramatically increase conversions and boost mobile UX.

"If a customer gets held up by a slow checkout, the sale is at risk." –Think with Google

Notifications

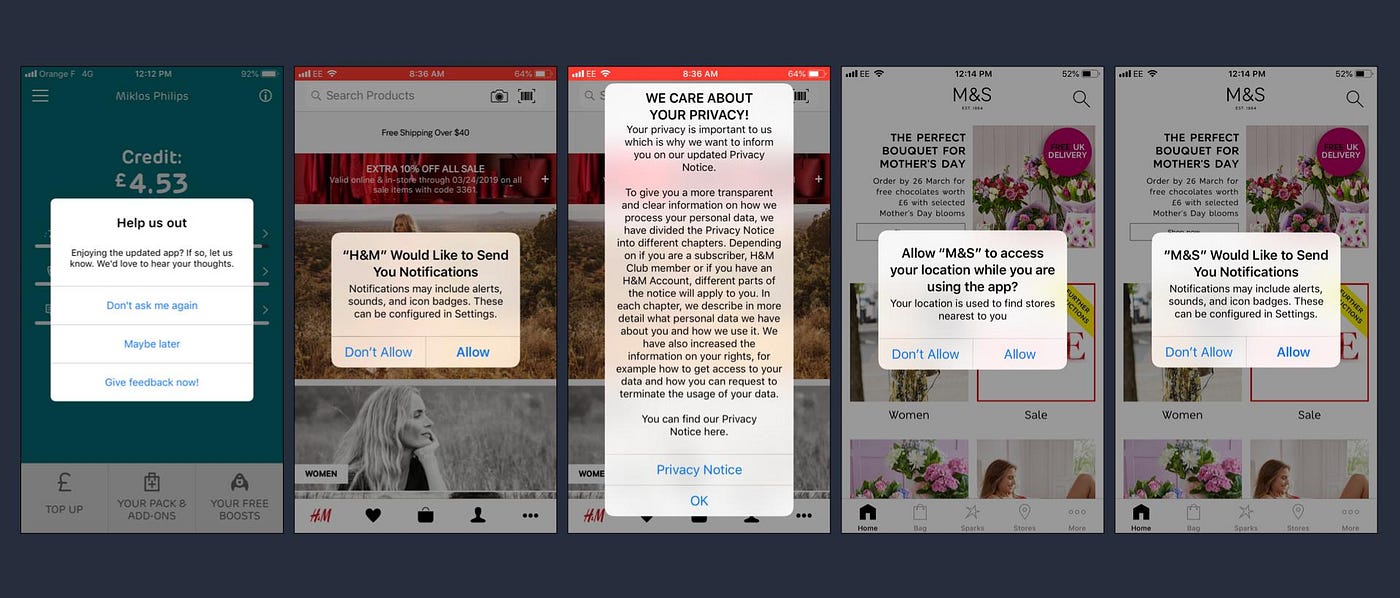

Notifications contribute to an experience that helps people accomplish a goal and should be treated like any other digital product component. However, notifications can cut both ways. If handled well, they can boost UX and assist engagement but risk becoming an annoyance when executed poorly. Striking the right balance is key.

Too many unnecessary notifications can frustrate users who may then silence notifications or stop using the app altogether. They are mostly interruptions, so it's crucial to look at the notification's message and how and when to ask for permission to send them.

The first app above asks users if they're enjoying the newly updated app immediately after opening it. The next two show H&M bombarding people, asking them to "allow notifications" and flashing a privacy notice as soon as they open the app. Marks and Spencer, another UK retailer (the last two), does the same. They are all examples of poor UX.

For mobile push notifications, the best practice is to delay notifications of any kind until people have had the chance to explore the app.

Mobile Interaction Design Principles

There's a fine line between an interaction that works and one that is unusable. Because usability is crucial on mobile, well-executed interaction design plays a considerable role in implementing great mobile UX. Observing interaction design principles takes on added importance as screens are small, and various form factors come into play.

Whether in digital product design or industrial design, design conventions are rooted in human behavior, ergonomics, and psychology. They follow best practices and expectations of how things work. These conventions have evolved by trial and error over a long time and are proven to be effective.

It's foolhardy and somewhat arrogant to ignore design conventions. Without them, we risk annoying people. Imagine if every bicycle, every door handle — or the pedals and the steering wheel in every car — worked differently, all purely in the name of "innovation." Designers need to consider expectations to reduce friction.

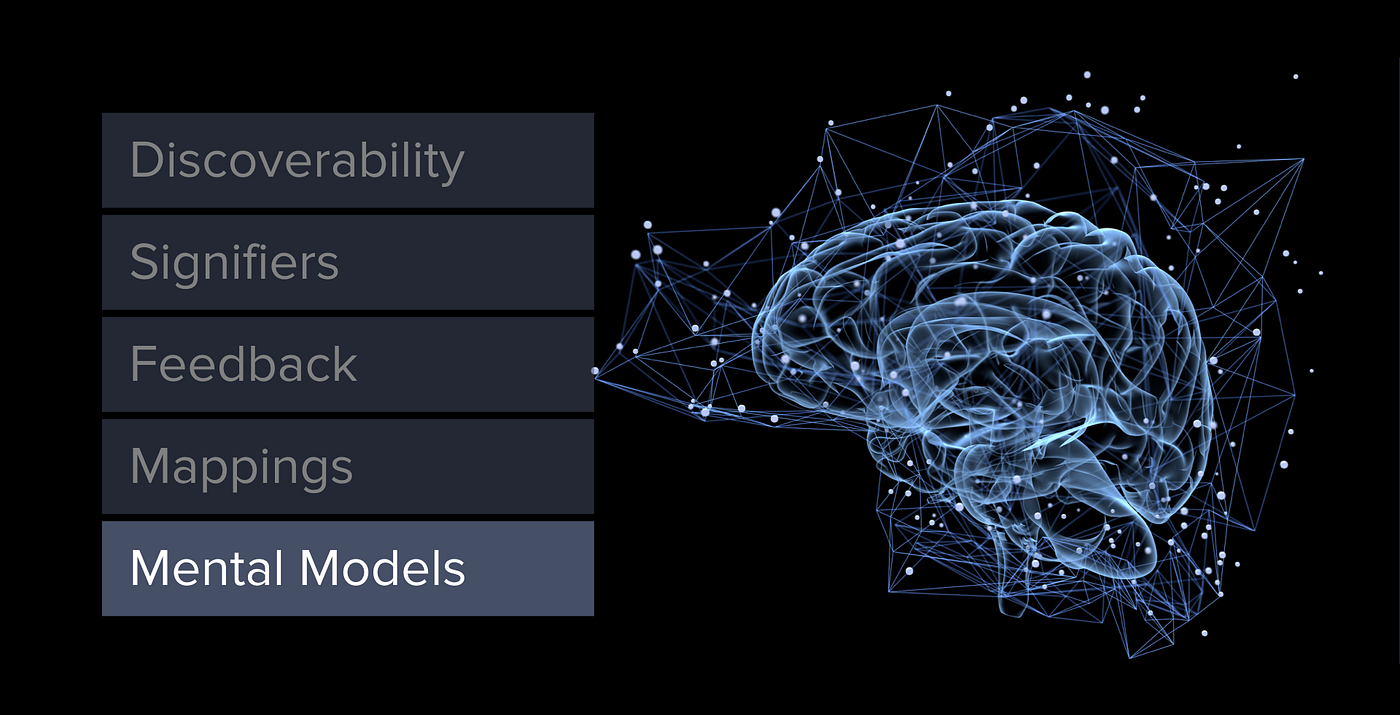

Discoverability — touched upon a little earlier — means: It should be evident what actions are possible from the UI and the current state of the device. Not just on the homepage, but on all the screens. Remember the kebab and hamburger menus and the unlabeled icons? They represent hidden or cryptic information. Designers should design UIs that let people discover features and interactions quickly.

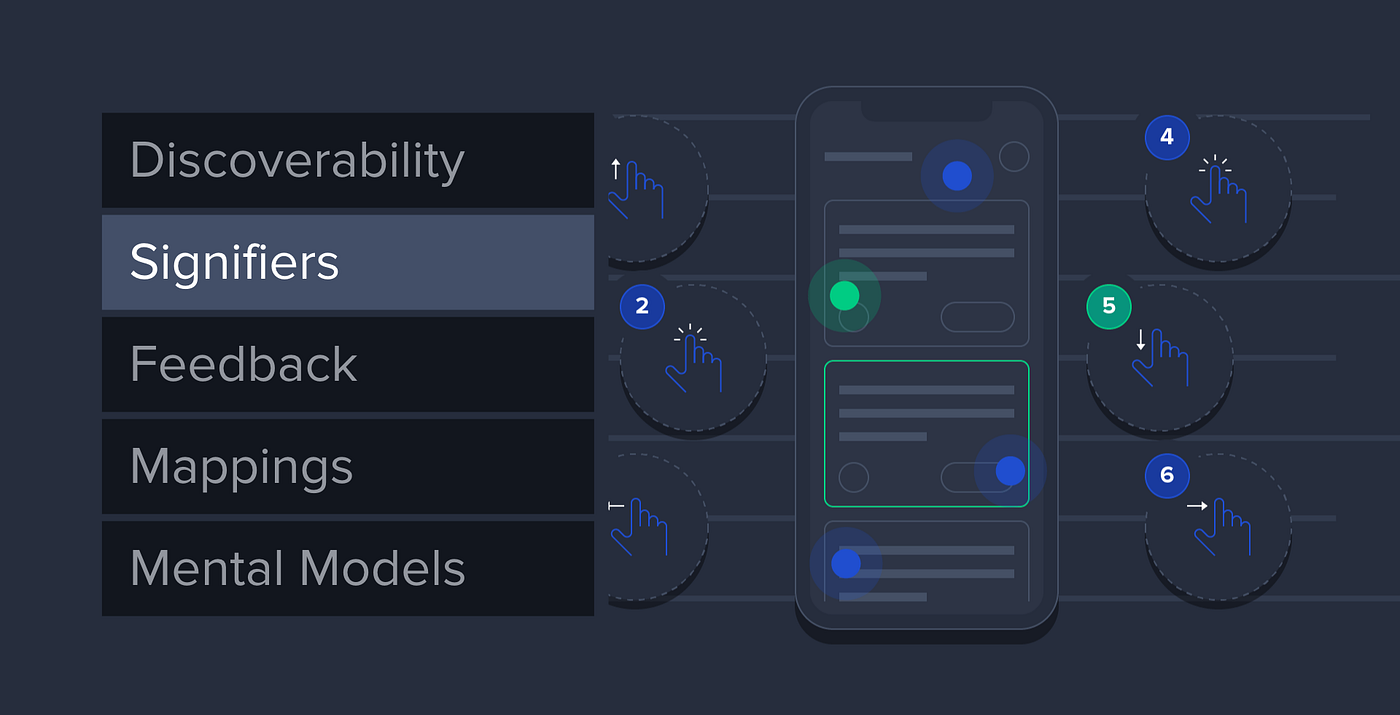

Signifiers. They are the clues or signals to affordances. Although this seems like a straightforward concept, it's one that seems to confuse people the most. People use the term "affordance" incorrectly all the time. In practice, designers need to use signifiers to indicate what affordances are present in a UI. A signifier can be a button, a menu icon, an input field, or an image that's just peeking in from the side of the screen, signaling — signifying — that users can swipe to it.

"Affordances define what actions are possible. Signifiers specify how people discover those possibilities: signifiers are signs, perceptible signals of what can be done. Signifiers are of far more importance to designers than are affordances." — Don Norman

Feedback. When we initiate something in the real world, we expect some feedback. Press an elevator button, and the button lights up, signaling that the system has received the call. Touch your transportation card as you get on a bus, and you'll hear a ding. It's comforting in many ways — it's the world "feeding back" confirmation to an action.

The same needs to happen in the digital realm. Feedback is closely tied to the usability heuristic "visibility of system status." Feedback may be visual, a sound, or haptic feedback, like vibration — for example, when you put an item in the shopping cart with Amazon's iOS app.

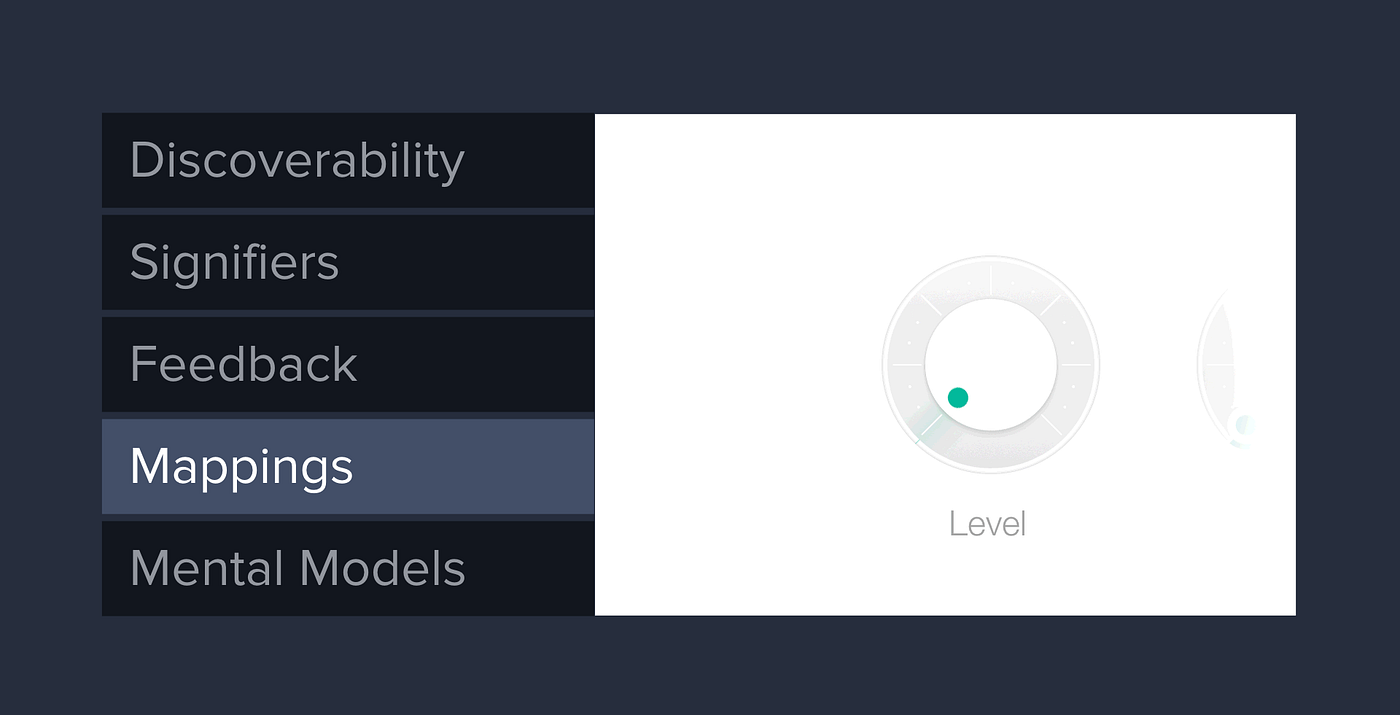

Mapping is about mapping UI controls to something natural — taking advantage of physical analogies and cultural standards in the real world. It leads to an immediate understanding in interaction design. One could call it "ergonomic UX." For example, a designer can use a spatial analogy in the UI: To increase a value with a slider component, swipe a slider up; to decrease it, swipe down. It's immediately familiar. People don't have to decipher meaning.

Mental models are also called "conceptual models" and are closely related to mappings. Remember what neuroscience calls "the lazy brain" and the case for frictionless design? Mental models are images in a user's mind that inform their expectations of a particular interaction and how something works in the real world.

For example, this Mercedes seat adjustment control is perfectly designed to align with people's mental models. It's immediately clear and usable.

When these interaction design principles are applied rigorously, they will provide excellent usability, leading to higher quality mobile user experiences.

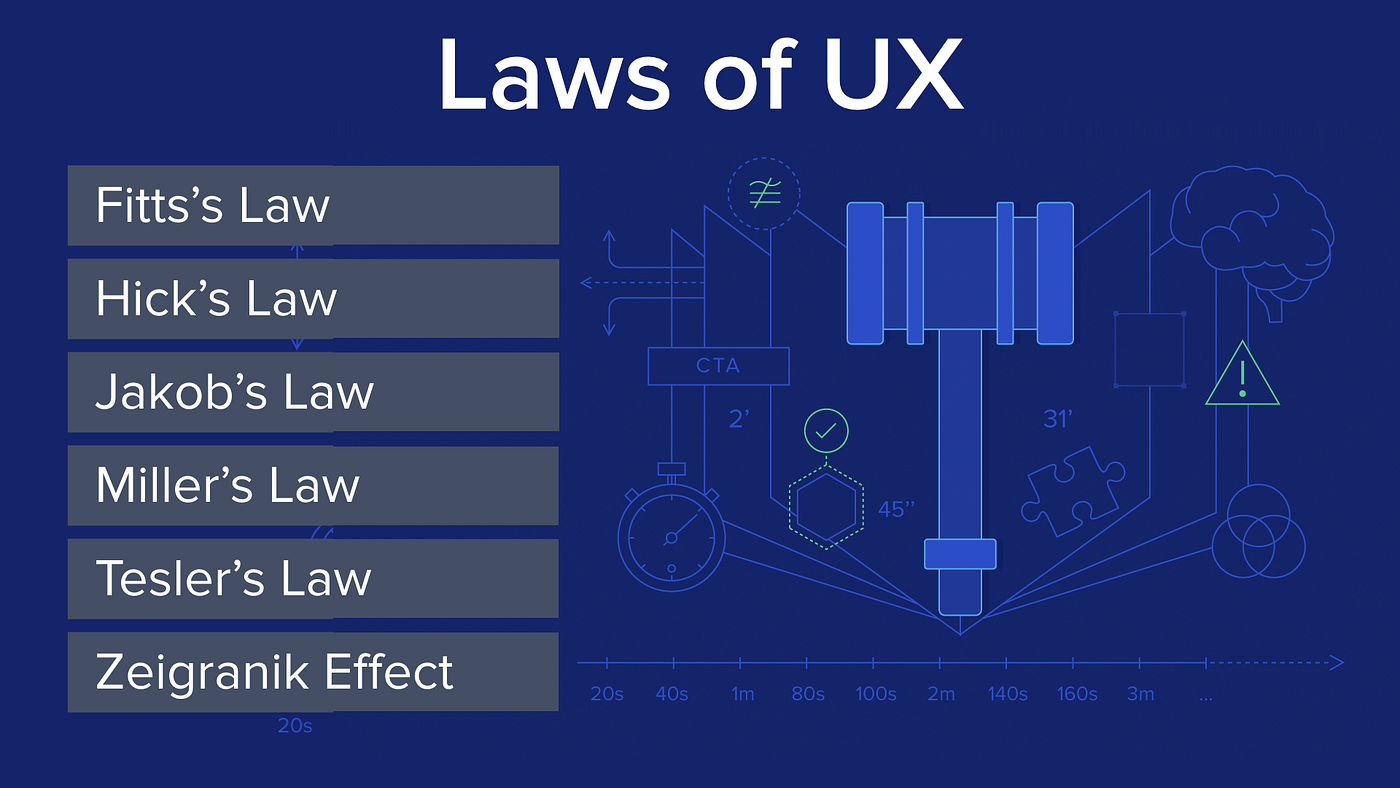

The Laws of UX in Mobile UX Design

Let's dive into six essential Laws of UX that mobile designers ought to observe and add to their arsenal. These laws are grounded in psychology and human-computer interaction science (HCI). Adhering to these "laws" is especially important for mobile sites and apps. Whether a UX designer acknowledges them or not, these laws of UX rule and operate and will impact a design's effectiveness.

Great customer experiences are based on trust and meaningful, consistent interactions. Any designer worth their salt must consider cognitive psychology and the effect of their work on their intended audience. For example, let's consider a bank with over 25 million mobile customers. In that case, it can be easily seen how ignoring the laws of UX could seriously inhibit their app's usability and consequently affect their bottom line.

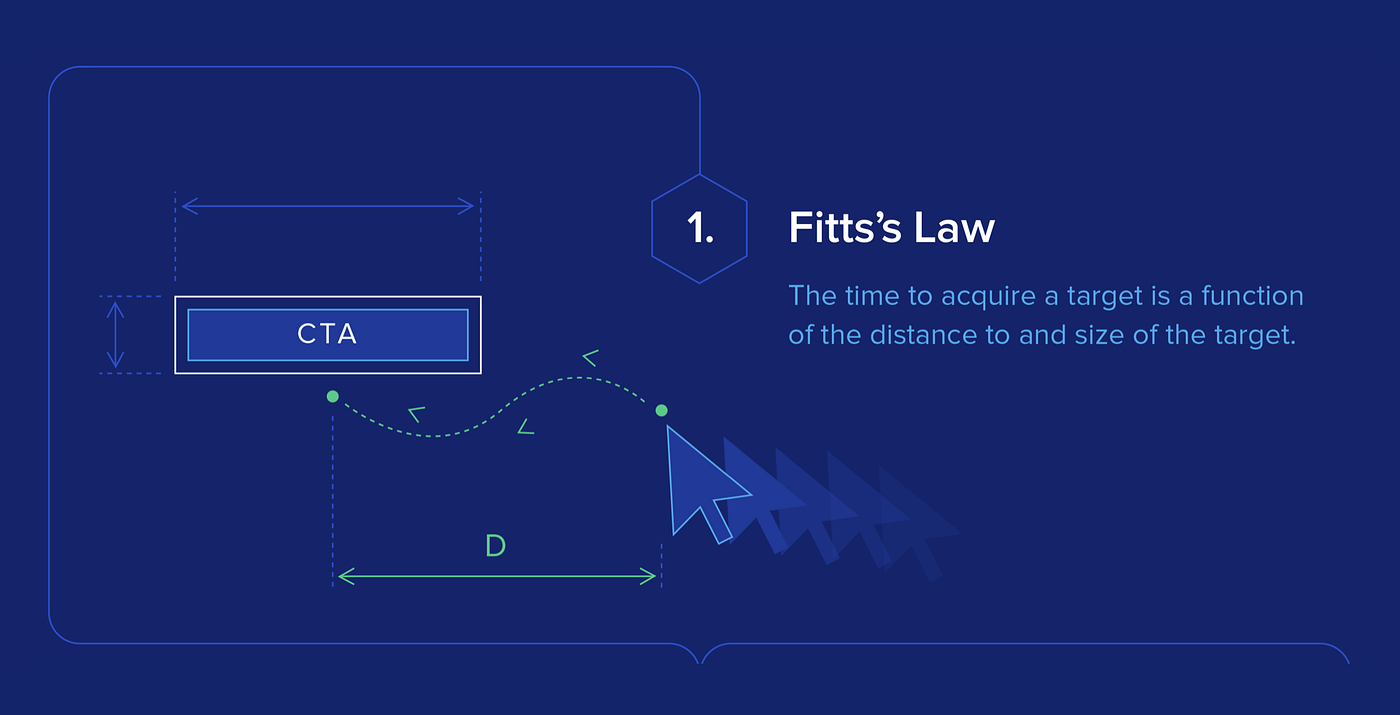

First up, Fitts's Law. It states: "The time to acquire a target is a function of the distance to and size of the target." Even though mostly applicable to desktop UI design, Fitts's Law can also apply to mobile UIs. The distance from one tap to another can be used to either assist or impede an interaction. For example, a destructive action such as "sign out" can be placed at the top of the mobile screen, and the confirmation can come up on the bottom. This would impede the interaction and provide enough time for the user to reconsider. Inversely, closely-related, non-destructive actions could be placed closer together to speed up interactions.

Believe it or not, this "law" comes from early studies looking at muscle movement and targeting by telegraph operators and was later adapted to HCI (human-computer interaction).

Hick's Law states: "The time it takes to make a decision increases with the number and complexity of choices." In a poorly designed scenario, this law could be violated by a UI that presents too many choices and asks people to remember too many things — for example, offering too many options to choose from when ordering something on mobile. Mobile UIs need not be simplistic but should be simple to use.

We saw this earlier, and it relates to the consistency of mobile UIs. Jakob's Law states: "Users spend most of their time on other sites or apps."

Designers can simplify the learning process by providing familiar design patterns, thereby increasing conversions. People expect a product to work like all the others.

Miller's Law states that "the average person can only keep around seven items in their working memory." When this rule is disregarded, people are forced to think more than they should have to. UX professionals often refer to this phenomenon as cognitive overload.

Ignoring Miller's Law can seriously cripple mobile UX. If there are too many things people have to remember, it could cause frustration and decision paralysis (aka "overchoice").

Lawrence Tesler worked at Xerox PARC in the mid-80s and was instrumental in developing the modern GUI, the foundation for Apple's Macintosh. Along with Bruce Tognazzini — another usability guy — he argued that when an application is simplified too much, people begin attempting more complex tasks. So, minimalist design is OK, reducing complexity is OK, but there is a certain amount of complexity that cannot be decreased.

This one is named after a Russian psychologist: Bluma Zeigarnik. The Zeigarnik Effect says that uncompleted tasks are easier to remember than completed ones. It turns out that our brain has a powerful need to finish what it started. Hollywood has used this trick for eons in episodic TV, known as the "cliffhanger."

For example, designers can use visual indicators for complex tasks that take longer — such as progress bars — to indicate when a task is incomplete, nudging people along to finishing it.

Taken collectively, observing these laws of UX can help guide a mobile UX designer toward creating the most effective design for any given product. Even though they are not actual "laws" but rather "tried and true" cause and effect relationships, mobile designers should nevertheless take notice of the driving forces behind the laws of UX to design superior mobile products.

Taking Advantage of Mobile Technology to Boost UX

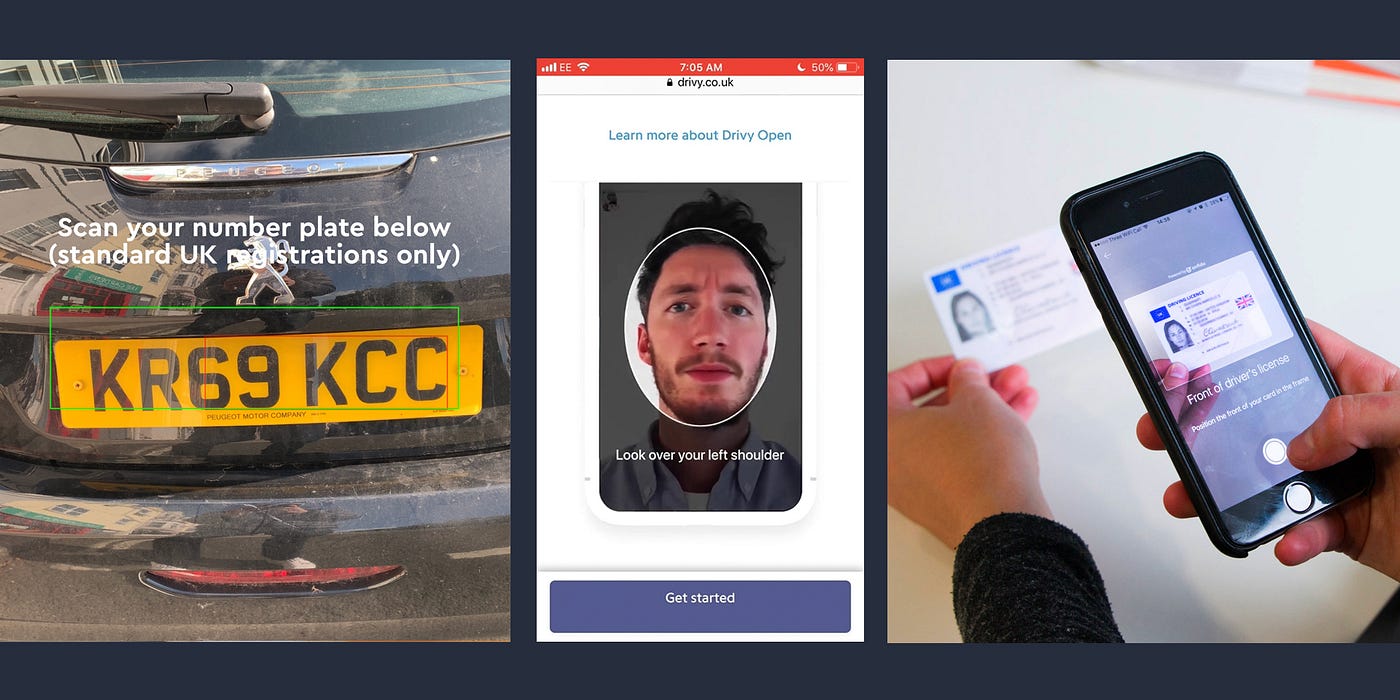

Last but not least: designers have other ways to boost mobile UX. They can take advantage of hardware components in a mobile device in creative ways to enhance user experiences.

All mobile devices have a camera that can be used for barcode scanning, computer vision applications, and augmented reality. We have motion sensors, GPS, accelerometers, compass, microphone, haptic and sound feedback, Touch ID, Face ID, Google Pay, Apple Pay, and so on — all of which could be used to enhance functionalities, improve feedback, and reduce interaction costs.

Summary

People are looking for convenience, ease-of-use, and efficiency when using their mobile. Too often, however, they're frustrated with mobile experiences due to poor usability.

As great mobile designs are becoming more prevalent, the bar is always being raised regarding what people expect from their mobile experiences. The best designers and the most successful companies use mobile UX design principles — to enhance usability, lower the barriers to adoption, and increase conversions.

It's about making mobile products work better.

Google 25 Principles Of Mobile App Design

Source: https://uxdesign.cc/boost-ux-with-mobile-ux-design-principles-and-best-practices-907e4f9fdd5d

Posted by: tranwhempos60.blogspot.com

0 Response to "Google 25 Principles Of Mobile App Design"

Post a Comment