Type 2 Compensator Design Tool

Andy Cruz and Rich Roat cofounded the studio in 1993, and have made a name for themselves in designing groovy fonts that nod to midcentury culture, including families inspired by Charles and Ray Eames, Alexander Girard, Richard Neutra, Googie architecture, and hot-rods. How do they do it? There's no hard-and-fast formula and no rigid playbook, but they do have a process-driven approach that's guided by a handful of loose rules.

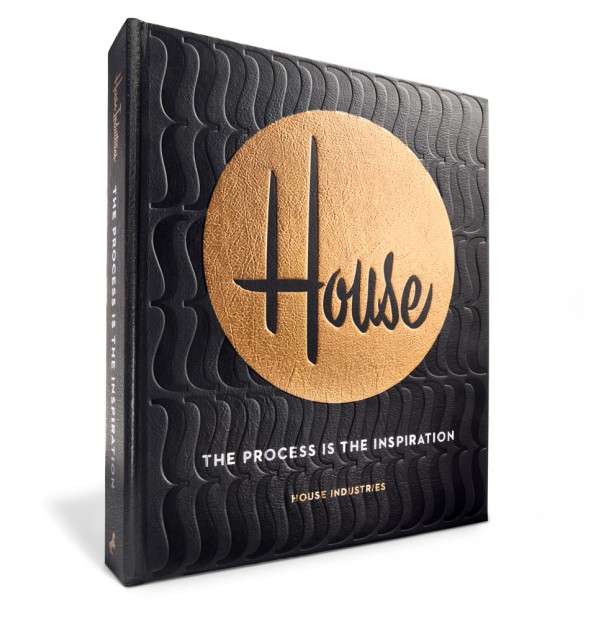

It wasn't until Cruz, Roat, and Ken Barber sat down to compile House Industries: The Process Is the Inspiration (Watson-Guptill, 2017)–a monograph detailing their design philosophy through case studies from their 24-year career–that patterns began to emerge in their work.

"Going through the process of decoding, and playing the record backwards so to speak, revealed what were were doing," Cruz tells Co.Design. We spoke to him to learn more about how House Industries creates its fonts.

1. Mine Your Personal History

In the book, Cruz writes that House Industries "built on the selfish notion of incorporating personal interests into our work." One of the most influential hobbies to House's aesthetic is hot-rodding. Cruz's dad restored Corvettes and brought him along to car shows, teaching him the science behind engines and explaining both the art involved in designing the body.

"The garage taught me the value of customizing a mass-produced machine and transforming it into a personalized work of art," Cruz writes. "House built a company on hot-rodding the alphabet, whether it was related to lowbrow car culture or highbrow modernism. The approach was the same; it was just the medium that was different." House's earliest work leaned heavily on automotive references, like its Rat Fink Fonts inspired by model car kits.

The personal histories of every designer at House seeps into the studio's work. Its Flyer fonts, for example, were inspired by Jeremy Dean, the first full-time designer Cruz and Roat hired. His history as a paste-up artist–someone who manually cuts and pastes type into layouts–informed the "anti-design" aesthetic of the font family, which looks like lettering you'd see on punk posters.

2. Make What You'd Want To Use Yourself

When House designs a typeface, it's often because it's looking for something that doesn't already exist. "They start off as selfish endeavors," Cruz says.

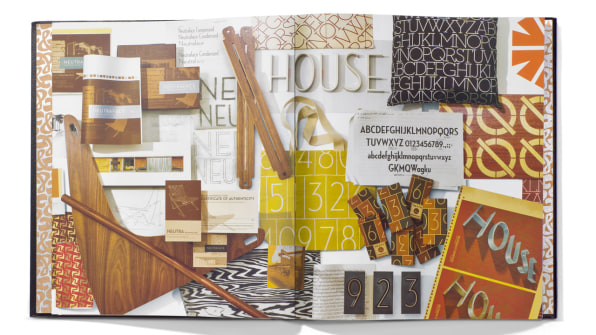

In the process of compiling the book, Cruz realized that many of the fonts House designed reflected how he was decorating his home at the time–some of the same things that caught his eye in his daily life were seeping into his work. This eventually led him to collaborations with the Eames Foundation, the Girard Foundation, and estate of Richard Neutra; and fonts that riff on the style of tiki bars (Cruz collects tiki mugs).

"I try to approach [design] history from a fan's perspective. If we are fortunate enough to collaborate with one of our heroes, I want to be reverent and do our best to share what got us excited about their work."

Meanwhile, what cars are to Cruz, bicycles are to Roat. This led to the Velo collection of bikes–with a frame by Waterford Precision Cycles, decals designed by House, and custom parts and accessories from Cinelli, Tanner Goods, Brooks, and Specialties TA.

3. Use The Right Tool For The Job

Cruz came to graphic design through illustration, and because of that the studio often leans on analog techniques like painting and ink drawing to arrive at their digital fonts.

"Money can buy fancy tools and special effects, but some of our most valuable tricks and techniques were born from a lack of it," the studio writes in the book.

Its Studio Lettering collection, drawn by Ken Barber, for example, nods to pre-digital design.

"If you want a form or stroke to capture the feeling of drawing or painting by hand, it's best to do that with an analog tool, then translate it to the digital world," Cruz says. "I feel that's one thing that humans seem to have a soft spot for—they might not be able to articulate it but can sense those considerations that add a little warmth or soul to a project."

4. Think Hard About Context

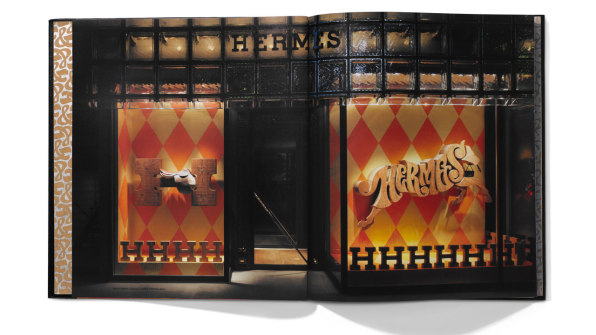

"Letter forms can trigger memories, experiences, and emotions. As manipulative as it sounds, depending on the image, [typography] can be used as a tool to provoke those sorts of feelings from a reader," Cruz says.

House's design work leans toward the evocative side, but that's because they know where and when to deploy exuberance and restraint. When Cruz took a call from Jimmy Kimmel to design his logo, he learned that Kimmel studied graphic design before going into television. That fact helped them develop a more adventurous aesthetic. For the New Yorker, they took a more subtle and buttoned-up tack.

"There has to be a sense of, that's cool, but is it right for this project?" Cruz says. "When does your personal taste outweigh or take a backseat to that thing we consider function? You've got to know the right time and place."

5. Declare Independence

Cruz and Roat met while they were both working at design firms in Wilmington, Delaware, but they decided that they could produce more creative work if they were their own bosses.

"We definitely knew we could make a living [in the corporate design world], but it didn't take very long to realize that it wasn't for us," Cruz says. "You can only do so many corporate design gigs when you're young and idealistic. As the magic faded, we started seeing opportunities that didn't have so many rules or focus groups. There was a much bigger design world out there we could play in."

6. Think Bigger

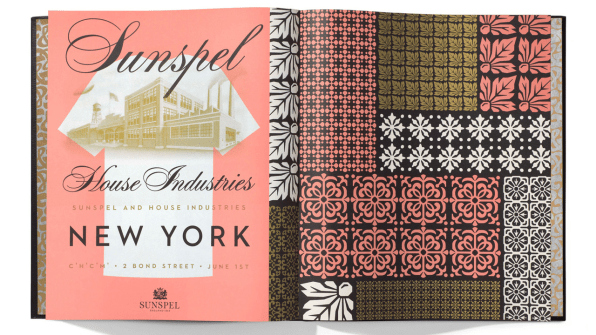

Fonts are the bread and butter of House, but the studio also designs three-dimensional objects and products including toys, house numbers, jerseys, and textiles. It's also in talks with a developer to work on a project at the architectural scale.

"Anyone who knows us might usually come in through our font door, but they soon find out that our design ADD doesn't restrict us from doing ceramics, bicycles, an interior, or even a satellite," Cruz says.

Now their interests are in getting more people interested in the hands-on processes behind graphic design through educational programs.

"You can sit and talk about your work and logos, but it's nowhere near as cool as seeing a 6-year-old or 66-year-old take our workshop and use their hands to letter their name or pull a squeegee and make their own serigraph," Cruz says.

7. Stay Forever Young

Part of what keeps House dynamic is that it approaches design with the same level of interest as someone who's just discovered the field–but with the added wisdom and experience of decades in the business.

"Honestly, I'm still doing the same stuff I was doing when I was 16, and I think that's what's kept it interesting," Cruz says. "We tried not to lose sight of the things that got us into design—whether that's illustration, or type, or packaging. It's all those little details that I dug that made me want to take a commercial art class in high school then continue learning through my interests, whether that was trying to make my car go faster or figuring out how to exploit the power of a printing press. We're still doing a variation of all of those exercises. The more I can stay in touch with my childhood, the happier I am."

Find House Industries: The Process Is the Inspiration on Amazon for $32.

Save

Type 2 Compensator Design Tool

Source: https://www.fastcompany.com/90131382/7-rules-of-great-type-design-that-any-creative-can-use

Posted by: tranwhempos60.blogspot.com

0 Response to "Type 2 Compensator Design Tool"

Post a Comment